My friends and I are all relatively new to Torchbearer, and are absolutely loving it so far, but one place we’ve been getting tripped up is the skills. Namely, we can’t seem to find any skill for stealth/ hiding or for perception of any kind. When those situations have come up, I’ve called for scout or survivalist or something, but it feels very ad hoc and like a bit of a stretch. Am I missing something? It seems weird to me that Weaver, Carpenter and Stonemason are all distinct skills, but there isn’t any readily available skill for sneaking or spotting things.

Hello and welcome!

The short answer is: nope, those skills are not missing, but it is a common question that really gets to the heart of what makes Torchbearer different from most other games.

You are right, though, that sneaking is absolutely essential to the game, but there is no prescriptive subsystem for it. It may seem counterintuitive or a miss, but there is a lot to discuss to connect all the dots.

What are skills?

The first thing is that the skills are based on trades/professions, background/class, and types of people in the world and are not constrained to individual activities. When you are testing Scout, it is because your character has some experience being a scout and that enables you to be a little bit better at things like sneaking or searching. So, scout has factors for stealth (DH, p. 173) which is usually a Vs. test, but depending upon the situation and the player’s description it could be a Nature test, a Health test, a conflict, a good idea, or perhaps some other skill.

DH, p. 72

“Skills in Torchbearer encompass a technique or profession, something you could practice and improve over time and that could be used to find work or really kill at parties.”

When do we roll?

The next big thing is that we mainly roll dice when there is danger, some uncertainty, some risk, or something interesting that might change the state of the game. If people want to search and there is no danger, just say, “Yeah, you find the book you were looking for.” or, “OK, you find a ladder leaning against the bookshelf, now what?”

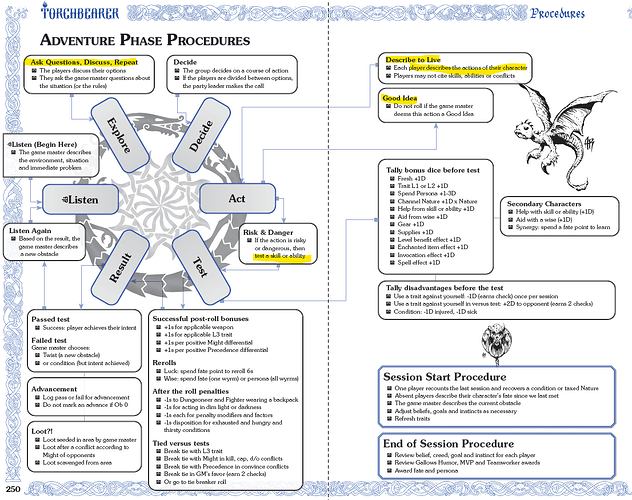

The chart on DH, p. 250 has a good flow of thinking about this. It says:

Risk & Danger

If the action is risky or dangerous, then test a skill or ability.

What is an Obstacle

The second part of this is knowing where your obstacles are. When you design the adventure you will create points where progress has to stop, a decision is made, and something changes. Something is blocking progress. Most everything else that doesn’t relate to that obstacle can be skipped or just given to the character. This is important because we do not want to accelerate the grind. If you keep a GM log of each test, it should read like the important beats of the adventure. Like, here’s the Laborer test where Beren lifted the giant log out the way to clear the debris blocking the door. And here’s the point where Ulrik’s lore mastery knowledge unraveled the mysteries of the ancient curse.

Not a Test and The Good Idea

“Not a test” and the “good idea” are similar in that there is no roll, but they are subtly different. There are some things that just don’t warrant a test. Just do it and move on. “Not a test” means that this isn’t something tied to an obstacle, and there is no risk–so let’s not roll. For example, if you need to travel from Rimholm to Olaf’s steading on the road, and there are no threats, then you just do it. There was no obstacle and so there is no test. Play on. Later, there might be bandits on the road awaiting in ambush due to some consequence like a twist or the reaction of some NPC. Now, you present the players with a new description and see if they investigate or ignore your clues. This could lead to a test or a good idea depending upon their description (see Describe to Live, SG, p. 214).

The good idea (SG, p. 216) is a way to circumvent an obstacle through clever play or to accelerate something that might normally call for a test but because of clever descriptions you can just speed things up to get to the next more interesting thing (see Obstacle to Obstacle, SG, p. 217).

The examples in the book are like, “Yes, you hide.” or, “Ok, you set a trap.”

So, my approach is to:

- Know where your obstacles are and keep driving toward that (everything else can take a backseat)

- Manage pacing with the good idea (keep the tension and pressure on the players)

- Balance the need to advance the grind and the players’ desire to advance their characters–you don’t want to cheat them advancement if the situation warrants it (it is risky and a true test of the character)

Check the Scout skill.

Wow, thank you so much for the very comprehensive reply! That makes a lot of sense, I think I just needed to revisit the books with a fresh set of eyes. I’m definitely still getting used to a system that expects you to roll a lot less than many others I’m familiar with, and that has so much tied into each test with advancement, the grind, twists/ conditions, etc. All the tests made each session forming an outline of all the important stuff that happened is a neat way to recontextualize that, I’ll definitely be keeping it in mind. Not a test and good idea are also just solid GMing practices that I should honestly be implementing more in general, so I’ll see about that too. There’s a lot to absorb with this game, but I really love how much it all interlocks and supports itself, and this seems like a really great example of that. Thanks so much for breaking it down for me!

Cool, glad to help.

Not sure what game your friends are coming from, but it is my experience that a lot of players from other games find comfort in rolling dice to make decisions. It becomes a part of the ritual of play. It can be a hard habit to break.

When I hear, “make a perception check,” that reminds me of that style of play. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, but it is a very different way of playing. In other games, players can roll to search an area and if they get a success, they are entitled to some reward because they “found something.” But in Torchbearer, if there is nothing there, then the player’s dice can’t suddenly generate something.

Also, players can’t call for tests. They don’t get to pick the skill that is being tested. For all of the above reasons, we can’t assume anything they do will necessarily trigger a test. But as you describe obstacles, you first give indications like this is a “steep, slippery, cliff” and then after calling for the test put a number to that. So, the GM always reacts, giving a little bit more information, waiting for more questions or descriptions, and repeating until they hit that obstacle.

New players from other games will often say, “I want to roll Scout to find traps” instead of saying what and how they do it.

Describe to live!

That makes a lot of sense. I’m coming from D&D 5e, Vampire: the Masquerade and assorted oneshot stuff like Ten Candles and Honey Heist, and all of my players have only ever played D&D, so “I roll perception” is kinda the only way we’re familiar with. Torchbearer’s way of doing things makes sense to me when it comes to PCs interacting with their environment, but I do still have questions.

For example, let’s say I have a Theurge with a high mentor stat who wants to teach another PC about the Immortals. During a time when their life and limb are not at stake (travelling, say) couldn’t the Theurge just… say they want to mentor the other player in Theologian by talking about the ways of the Lords? I feel like that would be pretty much the same as that player calling for a test, but I could be misunderstanding that. I get working towards the obstacle, but it seems like narratively speaking, the PCs should be able to act in ways that don’t necessarily advance towards that all the time. Again though, maybe I’m still stuck in a mentality that doesn’t apply here or am just misunderstanding things.

I think considering the phase structure of Torchbearer would be helpful here. There are rules for extended journeys in the Lore Master’s Manual, which are a little different, but otherwise you’re either in the Adventure Phase, the Camp Phase, or the Town Phase.

In the Adventure Phase, you’re somewhere harsh and dangerous and under the perview of the GM. This is where the action takes place, and the GM really needs to know what you’re doing specifically to match your actions against their view of the dungeon.

In the Camp Phase, you’ve earned a break and a chance to prepare youself for the dangers to come. This is much more the player’s realm. So instead of looking to the GM for information about the environment and the dangers pressing down on us to which we must respond, we look to the players to see what they do when they have a beat to take the initiative. So yeah, when the players have a break (like in camp), they can kind of call for tests. It’s technically still up to the GM (I believe), but we all kmow that tests are how you (usually) improve your position and that’s what you’re going to do here, so…

Saying, “I sit down by the fire with the warrior and give a quick primer on the immortal lords; Mentor test for Theologian?” and getting a nod from the GM – that’s a fine enough procedure. Then you spend the check, roll the dice, and apply the results of the test.

Town Phase is much like Camp Phase, but with Lifestyle being the currency for tests.

Hopefully that helps!

And welcome to the forums!

Considering the phase structure of Torchbearer would be helpful here

Yes, this is the way.

To add to all those excellent points: there are some actions that take too long to happen in the adventure phase under the grind, OR they shouldn’t come up because the adventurers don’t have all the necessary tools or equipment.

Like Gnosego said, Camp and Town phases are those moments of player agency when they are more in control. They can do those downtime things that take longer or require extra resources because they are not under so much pressure as in the adventure phase.

The game allows the GM the flexibility to interpret the situation, but we’re always operating under how skills work (see Inadequate Tools, DH, p. 74.)

An armorer might be able to bang out some dents in your breastplate while in the field, but they’ll need a forge to create a new set of armor. Similarly, a scholar can write scrolls and translate rune markings, but they’ll need to search out a library if they want

to do serious research and so on.

This means that the situation has to make sense. I am reminded of how things do not make sense in Baldur’s Gate 3, where you can camp at any point, even after only stepping right outside of combat. Torchbearer wouldn’t allow that because the situation is not resolved. You can’t do repairs, make camp, or do long actions in the middle of a conflict or until an obstacle or immediate threat is resolved.

So a player can’t say, “I’m going to make a new helmet” in the middle of the dungeon, without any new materials, and while a patrol of gnolls is nearby. They can’t just summon materials from nothing, although they have the basic tools like a hammer (see Necessary Tools for Skills, DH p. 73).

However, let’s say that there is a rusted helmet they find and they have some padding they looted. They want to craft a makeshift helmet in the adventure phase. Under the circumstances, the GM determines that there is no risk (no patrols or no nearby enemies) and they have cleared the area, so it is just a good idea. They now have a helmet, but knowing that it was makeshift, that could lead to other complications or being destroyed outright from twists later on if there is some failure or a consequence of a conflict.

Under normal circumstances in the Adventure Phase, there shouldn’t be an opportunity for someone to make new pieces of armor or do full training sessions because they are in constant danger and risk.

During a time when their life and limb are not at stake (travelling, say)

Bringing it back to the mentor test, this sounds like an action that is more than just mentioning some tidbits of knowledge. Depending upon the circumstances, you could describe days passing in town while the theurge pontificates and trains the mentee. But, you also have the Supply bonus (DH, p. 74). I would reward a player describing how there was some ad hoc training going on while traveling by granting a good idea that gives the character a +1D supply bonus to use later on because they took that extra time to describe how they kept teaching at every moment. I would look to the player’s description of what and how they did this and call it something appropriate like “Notes on the Lords of Fate (pack 1)”.

Ok, things are definitely starting to make significantly more sense now. My group and I are only 4 sessions in and none of us have played Torchbearer before, so there’s a lot we’re still muddling through and figuring out, but this really helps. Thinking of Mentor as a proper tutelage instead of some quick tips or bits of wisdom also makes sense, especially within the context of the three phase structure of the game.

In hindsight I think I’m guilty of somewhat homogenizing the phases: being too lenient during the adventure phase and not making the camp phase feel like a well-defined respite in contrast. I also need to lean more into describing to live, and thinking about the practical ramifications of an action and whether it would make more sense to happen during camp or town instead of the adventure phase. I’ve been feeling like TB is a bit of a contrast between very intuitive and very unintuitive mechanics, and I think this explains a lot of the unintuitiveness: I’ve been trying to play TB essentially the same as the game systems I’m more familiar with. In doing so, I haven’t been embracing the full philosophy behind what makes Torchbearer, well, Torchbearer. I’m gonna keep everything y’all have said in mind going forward, and I think it should really level up my game.

I also want to just say, thank you all so much for taking the time to help me out with this. I came here with a pretty simple question about a couple of skills, and I now have a much greater understanding of how this entire game works. The community on here is so welcoming and helpful, and I really appreciate that.

Looking at your example of talking about the ways of the young lords, I would pressure the players to find the tension. It’s not going to prompt a test to just talk about their (the theurge’s and the other character’s) beliefs about the old ones, the immortals, the young lords, etc… They’ve got to establish whether there is tension and what is the tension about.

Here are some ways players might dive deeper:

“You should not have taken that idol of Vali Kinslayer! It’s not going to be good tidings for us when we visit the next town, and your bag slips open to reveal an idol to the lord of murder.” See, now this is a moment of tension, and it could prompt a test of Mentor to preach about the ways to show reverence without carrying around an unlucky or cursed idol.

“I cannot believe you held me back from prying the gems from the Eye of Harpa! It would fetch a fine fortune when we reach the next town. You owe me something for it. I think it’s worth at least a steel sword or a fine cloak.” See now you’ve got some tension that might prompt a Haggler test or maybe a Manipulator test.

“The old ones are worthy of honor, but the young immortals were all power-hungry cultists! I’ll teach you to dishonor the shrine to the old ones; you had better spare some treasure for the shrine at the next town. If not, we’ll be cursed for sure.” See, there’s some tension that might prompt a Mentor test or maybe a Persuader test.

“It is a good thing we found the aetir’s mark in that tomb; it proves the warrior buried there is of the same clan as the folk from that last town. We should go back to humble them and command them to clean up the site and honor their sacred dead.” Now, this is a bit less tension, but if they want to convince everyone to turn back, visit the last town, and allow some preaching, maybe it is a good candidate for Mentor, and might lead to Orator and Theologian a bit later (if it didn’t call for Theologian while in the tomb identifying the mark).

“I’ve seen that mark before, that we found above the tomb. It is the mark of a dead clan. We could claim to be of that clan by using the loot we recovered. It would grant us some prestige in the last town we visited–it would have been their folk. We could enjoy some luxury at their expense at least.” This may not have much tension, but could prompt a test of Persuader and later a test of Orator, and might have required a test of Theologian while in the tomb.

Contrast those above with some of the simpler expressions of talking about the ways of the lords:

“While we’re here at camp, I feel I must preach to you about honoring the young immortals. Have you been touched by Harpa, the Spring Maiden? Do you understand the blessings you could have under her care?” See, not much tension, but it’s as though the player wants a Mentor test. What’s the possible outcome? Just granting a pass/fail to an adventuring companion. I mean, I’d allow it as GM, but I would try to pressure the players for more depth. What’s important about religiosity to the other characters? Will it prompt a new BIG? Will it cost something?

“Before we all rest, I must insist of prayer and purification for all. Please join me near the water’s edge. I will conduct the ritual and preach while we eat a ritual meal together.” It could prompt a Mentor test, maybe a Theologian test instead. But, why does it matter? Is is just a characterization? Are they in need of purification before some other conflict? Is it going to work into their cult worship of an aettir? There are some possible options, but it is rather low-risk.

As GM, I would allow players to build the tests they want during Camp or Town phases, and sometimes during Adventure phase. I try to listen to the table chatter to help them generate the scene that calls for a test. Not every test must be cinematic and climactic. It’s alright to have calm and subtle scenes where a test has low risk or only minor bearing on the adventure ahead.

After reading the comments I still wonder how this game should be played regarding skills and choosing them. I of course have had my way but still I am curious to know how you deal with this.

If

“Skills in Torchbearer encompass a technique or profession, something you could practice and improve over time and that could be used to find work or really kill at parties.”

Then there will always be several different options or techniques to use in different obstacles.

How would I as a game master interpret this to the flow of game. According to flow in pages 30-31 SC: “Once you know the problem to overcome and what youll do to conquer it, the game master assigns the test to specific skill or ability”. I have used this in my games and tried always to find best suitable skill with fitting factors to situation. This sometimes lead us to discussing if other skills could be used and some times it is difficult to draw a line.

If example, group encounters a giant in the gate of a dungeon. I as a GM would describe this to life. Then players would describe their plan to try to befriend the giant. Is it first up to players to also choose appropriate skill (circle, nature, even peasant) after which I then as a Gm accept? Or will I as a GM determine the skill first?

Some skills are irritating because they are so close to each other like hunter and sapper. It is unfun to tell a player that has master-hunter character that cannot even make a rabbit-trap. This is maybe a whole new subject but affects the flow also.

The GM determines the skill; players should always be talking in terms of action and not in terms of skills (DH 20).

There is some overlap. In cases where it’s unclear to me as GM which skill best applies, my first step is to get more specificity about the characters’ actions. Often thar clears things up nicely: “What do you mean, ‘make a rabbit-trap?’ Are you setting snares at rabit-sized trails through underbrush? Are you setting up a crossbow rigged to tripwire?” The former is clearly Hunter – snares 1 + small animals/monsters 1 – the latter clearly Sapper – crossbow mechanism 4.

Some cases are not so easy to disambiguate: “I rig up a big rock on a figure 4 deadfall (Hunter: Deafall 3; Sapper: Deadfall 3).” In such cases, I might look at fine-grain nuances in the skill, which tools a character is using in the test, and their motivation for their actions. Hunters use traps to capture creatures; Sappers use traps to defend dark tunnels underground. Are they underground? Do they want to capture or defend? Are they using Sapper tools or Hunter tools (or something else?). If I’m not sure after drilling down into the specifics, then I might give some options to the player, but I see this as more of a last resort.

There is more than one way to overcome an obstacle, yes. Generally, though, dungeon-crawling falls into predictable situations. So, although there are infinite ways to describe something, we have a finite list of skills.

to find best suitable skill with fitting factors to situation

Using the listed factors is a great guide, yes! When we talk about “knowing your obstacles,” there should be some sense for how an obstacle normally would be overcome.

But when something doesn’t fall neatly into those skills, your options are:

- No test

- Good idea

- Ability instead

- Nature instead

- Beginner’s luck

- Some other skill substitute if appropriate

Let’s stick with sneaking for an example. The class Halfling Guide (Scavenger’s Supplement, p. 20) does not have the Scout skill but has the sneaking Nature. The GM describes guards in the middle of the room. The characters need to sneak past the guards or get around them. The player describes the character naturally hiding in the shadows and using the crates as cover to sneak past them. Normally, this would be a scout test but since it is within Nature, the player can test sneaking instead.

Now, let’s say the player gets crazy and wants to swing from the rafters. Is there still a risk? If so, where is the risk? Is it in being detected? Is it climbing up to the ceiling? Is it lasso-ing the whip to the crossbeam? Where is the most tension? Where are we blocked? What and how they describe their action determines what is being tested. Again, you go through that list of options. If you decide there needs to be dice involved, you roll dice at the moment you have clarity.

Note, you can always test your nature if you don’t have the skill the GM calls for. The key difference is that if it’s within your nature, as in @Koch ’s sneaking example, it doesn’t risk taxing your nature. If it is outside nature, it is taxed by margin of failure if you fail.

Thank you for your replies.

You had good viewpoints to this issue. From what I read I would build the flow as follows:

- Introduce problem and describe it to live

- Players describe their action (not in terms of skills)

- Optional: If description is vague and there is more than one suitable skills to apply in this situation Gm asks more description.

- Gm detrmines skill, or ability and factors used.

- Player can decide to use skill or nature.

And following this it is up to player to describe his actions so it fits with specific skill if he wants to use that skill. For example with hunter and sapper, player should describe rabbit-hunt situation so that it fits the skill that he is good at. Of course sometimes you just cant make it and the situation forces you to use specific skill

I dont know how you play with your group but we usually have played so that after initial description, playwrs can later add more to that description to be able to use traits or nature. It complicates the flow and slows the game but make descriptions interesting

I think that this list below is a good one until number 4. I think gm should never state that this obstacle is tested with specific nature. That decision is up to players to make.

- No test

- Good idea

- Ability instead

- Nature instead

- Beginner’s luck

- Some other skill substitute if appropriate

Just to clarify a couple of points…

Player can decide to use skill or nature.

When substituting Nature, you cannot choose to use Nature if you have that skill. If you have the skill, you need to test it. Otherwise, the player can decide to test Nature (see Acting Within and Outside, DH, p. 66) after the GM calls for a test.

gm should never state that this obstacle is tested with specific nature

Yes, that is right. The GM calls for a test, such as a Scout Ob 3, and then players can decide to substitute Nature if they don’t have the skill.

Looking back, my list was not clear. It was not meant to be a linear GM checklist. The point I was trying to make was in response to your OP: “there will always be several different options or techniques to use.” I was just pointing out that there is indeed more than one way to overcome an obstacle. I see GMs make the mistake when designing an adventure of thinking that an obstacle in a room can ONLY be solved by the test that they originally wrote down (e.g. only a Scout test to get past the guards). But that is not the case. The GM needs to react to the description and call for the test that best matches.

The diagram on DH 250-251 is the best guide:

For the Ask Questions, Discuss, Repeat part of the adventure phase, if the players explore something that is not headed toward a test, then there is no need to go through the Decide or Act procedure. Discuss it and move on without a test.

Player: “I want to sneak to the bookcase to check for any clues, such as pieces of paper.”

GM: “The bookcase is empty. You check all around, and there is nothing there.”

Player: “I want to block the door. Can I spike it shut with my iron spikes?”

GM: “Yes, OK. You use one spike to jam the door closed. What next?”

These things fall under the Explore step and aren’t tests against the obstacle. There is no risk or complication.

However, after they interact with the obstacle of the area, that is a different story. With the guard example, they players need to decide how to get past the guards and describe it, but before the GM calls for a test, the GM needs to determine if the description circumvents the obstacle with a good idea:

- See the Good idea under Act

Player: “I use my potion of invisibility to sneak past the guards.”

GM: “Great, that’s a good idea. The guards are too busy gambling to hear anything, so you make it safely to the other side of the room.”

There was an obstacle there but because of the specifics of the situation, there was no need to call for a test. Under different circumstances, there could have been a test if the guards were on high alert or if some beast had super hearing. Then the potion could provide a bonus to a Scout vs test if it was still risky and uncertain.

At the end of the Act step, the GM calls to test:

- a skill

- or an ability

For example, if the obstacle is getting past the guards, and someone just runs for it, the GM might call for a Heatlh vs test to see if they can rush past the guards in time. Whereas, if the player described sneaking the GM would call for Scout vs test.

After a test has been called for that a character does not have the skill, the player may opt to:

- substitute Nature

- use Beginner’s Luck

So I think we’re saying the same thing, sorry for any confusion. But there are some things the GM needs to think about and then there are some things that are player choices, yes.

I have a question that I’m curious about regarding the “Sneak past the guards” example. Let’s say a party of 4 wishes to sneak through the room without being spotted. Would each player need to test Scout to get through unnoticed, or would one player test Scout for the entire party?

I’ve found this statement:

“Or, if they devise a plan, determine the step of the plan involving the greatest danger and make them test then.” SG 214 Walking Into Danger

does a lot of heavy lifting for me. I have applied that to considering, “who’s in the greatest danger as they’ve described their sneaking,” and had that person test. If there’s no one that stands out, I I’d throw it to the person who took the lead. (As per Never Volunteer, SG 31.

So, that is to say, it’s one test for me. ![]() I really try to keep things to one test to overcome the obstacle – outside of traps and conflicts.

I really try to keep things to one test to overcome the obstacle – outside of traps and conflicts.

I agree that trying to find the highest point of tension and making a single test is the best way to go most of the time.

However, if the situation calls for it, you can treat it as an individual independent test (everyone rolls, no help because they are on their own, but one turn on the grind). This would be a “sprung trap” situation (Traps and Landslides, SG, p. 40) where the guards were suspicious after some noise or event and now everyone has to scramble for cover to avoid notice.

If the stakes were really high, you could also treat it as a custom Other conflict.